The recent newspapers warned us about an epidemic in India, and in particular in the Kerala region. The responsible is the Nipah virus and it caused the death of about ten people in a few weeks. We are told that “the Nipah virus is fatal in 70% of cases”. What is this virus? What should we really fear? How does it relate to influenza, Ebola or hemorrhagic viruses? We will try to answer these questions.

Nipah virus

It is an RNA virus belonging to the large Paramyxoviridae family in the same way as the mumps virus or the measles virus. Together with the Hendra virus (responsible for acute equine respiratory syndrome), it forms the genus Henipavirus. It was then determined that Pteropus fruit bats were the most likely source of infection with 47% seroprevalence, no other species being positive. contamination is via saliva, urine and/or amniotic fluid from the animal.

Nipah virus was first identified in 1999 during an outbreak of encephalitis and respiratory diseases among pig farmers in Malaysia and Singapore in 1998. It takes its name from the Malaysian village of Sungai Nipah where the first sick farmers came from. During this epidemic, 115 people out of 265 infected died and it was the euthanasia of one million pigs, the intermediate host, that contained the disease. The killing of the animals led to a considerable commercial loss. The same bat that hosts the Handra virus can also harbour the Nipah virus and contaminate the food of the pig, which, by coughing, spreads the virus around it contaminating humans. During this epidemic, symptoms of infection were respiratory in pigs and encephalitis in humans.

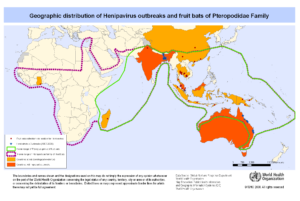

The bat’s natural habitat is geographically distributed in an area encompassing northern, eastern and southeastern Australia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and some Pacific islands. On the map below, we can draw a parallel between the bat’s habitat and the infectious cases of Hendra and Nipah viruses.

Outbreaks

The first outbreak described, in 1998-99, occurred in Malaysia and Singapore. No other cases, neither pig nor human, have been reported in these 2 countries any more.

In 2001 an epidemic broke out in Bangladesh with a Nipah virus genetically different from the previous one. The same year, another epidemic broke out in Siliguri in India and a man-to-man transmission was even described. Unlike the epidemic in Malaysia, outbreaks are regularly described in Bangladesh and India.

The latest epidemic currently in progress has claimed 10 victims in 2 weeks and villages are isolated from the rest of the world. It is the Kerela region of India, which is currently under attack from a particularly virulent virus. The epicentre appears to be the village of Kozhikode and 1,300 people who have been in contact with infected people are under surveillance.

Since it was described, an estimated 250 people have died from the virus. Of mortality similar to that of the Ebola virus it kills on average 7 patients out of 10. In fact, the relatively low number of deaths to date can be explained by the fact that the virus kills very quickly, preventing its spread and also because the populations most at risk are herders living in rural areas and travelling less than businessmen…

Transmission

This deadly “emerging” virus is harmless to its natural host, the bat. It is excreted in saliva and urine and has a marked preference for pigs. This is why the first cases of transmission to humans occurred among pig farmers in Malaysia and Singapore. It should also be noted that in none of the subsequent epidemics was the pig used as an intermediate host: the virus passed directly from the bat to humans. The animal is a great lover of palm sap which it can contaminate. By climbing up a contaminated tree or drinking palm sap, man can in turn become contaminated.

Now, man-to-man contamination is common, via contaminated fluids. The latest victim is a nurse infected by the patients she was caring for.

It is very likely that the proximity of the places where bats and humans live, particularly because of deforestation, is at the origin of these epidemics.

Pathologie

In humans, Nipah virus infection is associated with encephalitis (inflammation of the brain). The incubation period is 5 to 14 days. Clinical signs last between 3 and 14 days: headache, fever, drowsiness, disorientation and mental confusion. These signs can lead to coma. Some patients may show respiratory signs during the early stages of the disease and more than half who have neurological signs also show respiratory signs.

Long-term sequelae have been observed such as persistent convulsions and personality disorders.

Without specific treatment or vaccine, intensive symptomatic treatment remains the main method of infection management in humans.

Conclusion

The main host, the bat Pteropus, whose territory is relatively small, the relative difficulty of transmission from the bat to humans, the very rapid mortality and the rather isolated location of infectious outbreaks seem to indicate that epidemics with Henipavirus, (Handra and Nipah virus) are not in the capacity, for the moment, to give large epidemics such as those of influenza or Ebola. However, the evolution of emerging viruses is very difficult to predict and that is why the Nipah virus is in the top 10 diseases likely to create the next major epidemic, according to the World Health Organization.

For the meantime it seems that the authorities are in a position to manage the situation, but we can refer to Ebola epidemics, for example, to see how a stable situation can suddenly get out of control.

Personnal protection equipment have been proposed: PPE

References

http://www.who.int/csr/disease/nipah/Global_NiphaandHendraRisk_20090510.png?ua=1

https://asiancorrespondent.com/2018/05/india-what-you-need-to-know-about-the-nipah-virus-outbreak-in-kerala/#QaoHDedr4Dl4hl3T.97

S.P. Luby, E.S. Gurley, M.J. Hossain, Transmission of human infection with Nipah Virus, Clin. Infec. Dis., 2008, 49, 1743-1748

M.J. Hossain, E.S. Gurley et al. Clinical presentation of Nipah virus infection in Bangladesh, Clin. Infec. Dis., 2008, 46, 977-984

P. Chatterjee, Nipah virus outbreak in India, The Lancet, 2018, 391, 2200

Autor: Prof. François Renaud